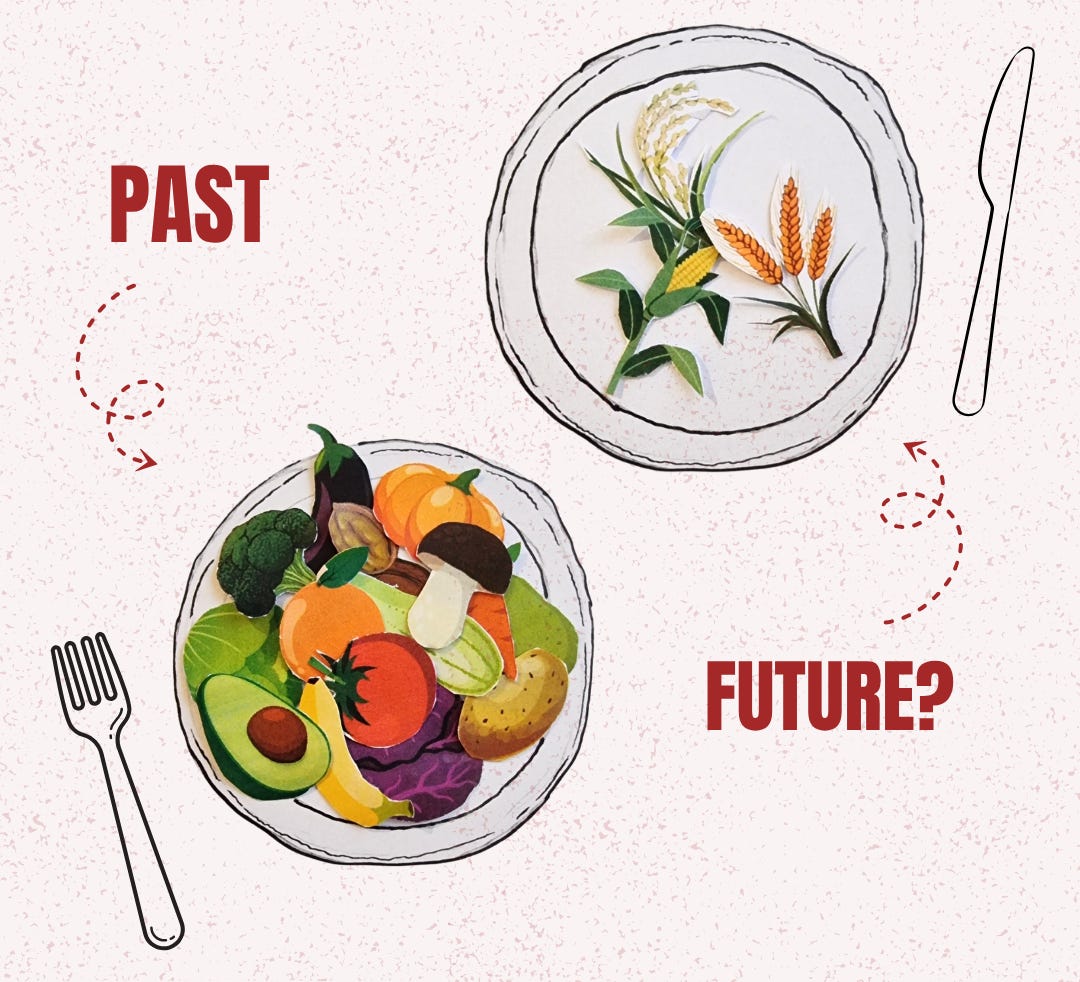

What if you were only allowed to eat 5 plant species?

We're heading there...

Coloured diets with plenty of plants usually indicate a good variety of nutrients. Eating 30 plants a week, as is often touted1, might seem a bit too daunting, but can you at least get to more than three?

Of the estimated 30,000 edible plant species on the planet, 7,000 are estimated to have been cultivated or collected by humans for food at a certain point in history.2 However, today, 75% of the world’s food is generated from only 12 plants and 5 animal species!3 What’s more, over 40% of our daily calories come from three staple crops: rice, wheat, and maize.4 Not only species, but also their varieties, are heading into oblivion. Did you know that there are thousands of varieties of apples, rice, tomatoes, or potatoes? How many do you frequently find in stores?

Monocultures are an easier, faster way to feed the growing population. And with the main goal of productivity and increased sales, high-yielding and uniform varieties are ever more valued. But we should know by now that “haste makes waste”. What are we sacrificing?

Resilience

Natural selection has been working its magic since life first appeared. Species that are not adapted to the local environment will be selected out, while species with characteristics that make them thrive in that environment will survive. This is the basic mechanism of evolution.

In a changing environment, and especially in the fragile situation the planet is currently in with climate change, food diversity is an asset. In the event of a catastrophe, like a pest, drought, or war conflict, a group of different species/varieties is more likely to include some specimens that can survive. Instead, if we depend on only a few crops, one catastrophe could decimate global food supplies.

Nutrition

Different plants provide different nutrients, so the higher the variety of plants in a diet, the more likely it is that it covers all nutritional needs.

Cultural heritage

Traditional crops result from a careful and laborious selection by farmers and gardeners. Furthermore, throughout history, they were used for traditional recipes and passed down through generations. Losing crop diversity is losing this heritage too.

Taste and quality

Crop diversity translates to flavour and recipe diversity. Additionally, most of today’s varieties have been selected for their uniformity, fast growth, or other selling points. This can be at the expense of other qualities, such as nutrient density and flavour.5

Preserving biodiversity

Thankfully, there are still some heroes fighting to save the biodiversity that is left.

Seed banks

Seed banks are places where thousands of backup seed varieties are stored in secure and cool environments, so that some biodiversity might be rescued in case of emergency. One example is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, a storage unit located deep within a mountain that keeps frozen seeds from across the globe.6

Although these projects are super important, it is even more urgent to preserve the biodiversity we have today and to continuously store new seeds. Who can say if the varieties kept in a seed bank will still be adapted to the climate at the time when they are needed? Or if the pollinator they depend on will not be extinct?

Slow Food

One of the priorities of the Slow Food movement is to protect diversity, both biological and cultural (the latter referring to products, knowledge, or traditions).7 For example, the Slow Food’s Ark of Taste is a catalogue of traditional foods around the world.8 By raising awareness about these foods and traditions, they help keep them alive.

Heirloom gardens

Before industrial agriculture and its large monocultures, a much wider variety of plants were grown. Their seeds were selected and passed down by farmers and gardeners. Today, some of these older cultivars, named heirloom varieties, are still maintained through generations.

In contrast to commercial seeds, these varieties have often been selected for flavour, suitability to the local climate, and cultural significance, rather than their uniform appearance or shelf life.

Another aspect that makes these varieties so valuable is that you can save their seeds to grow the exact same plant. In contrast, for some commercial varieties, this is not possible, so farmers depend on whoever sells them seeds or the varieties.

Further reading

If you’d like to continue exploring the subject, here are some resources I recommend:

Seed banks around the world (photo essay by Food Unfolded)

Thank you for reading. Let me know in the comments if you have any questions or if there is a particular subject that you would like to see covered in this newsletter! Feel free to share this newsletter with whoever you think might find it interesting.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/food/articles/plant_points_explained

https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0172f037-db3b-47e8-9f93-26a1701db513/content

https://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2019/pr-2019-05-22-idb-en.pdf

https://www.fao.org/newsroom/story/Once-neglected-these-traditional-crops-are-our-new-rising-stars/en

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/fruits-and-vegetables-are-less-nutritious-than-they-used-to-be

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/cryopreservation-plants-extinction

https://www.slowfood.com/about-us/

https://www.slowfood.com/biodiversity-programs/ark-of-taste/